Author: Caoimhe Mcloughlin.

Stigma in persistent somatic symptoms and functional disorders (PSS/FD) has been around for centuries. In earlier times, individuals with these symptoms were accused of moral failure or spiritual possession – much like other conditions that seemed hard to understand, such as epilepsy or tuberculosis. In more recent times, individuals with functional symptoms were (and still are) accused of faking or exaggerating symptoms – and many are simply rejected by clinicians and society, and considered undeserving of care.

Despite clear evidence of this stigma throughout time – it is only relatively recently that the extent of such stigma has been brought to light – mainly by patients, but also by clinicians, caregivers, researchers and advocate groups.

Stigmatisation is a complex social process that acts from a position of power, and is dependent on lots of dynamic factors – social, cultural, historical, among others. That said – the encounter between patient and clinician serves as a pivotal moment during the patient’s health journey. Clinicians hold a position of power in how they both listen to and impart information – how they enable the patient to feel heard and understood, or dismissed and blamed.

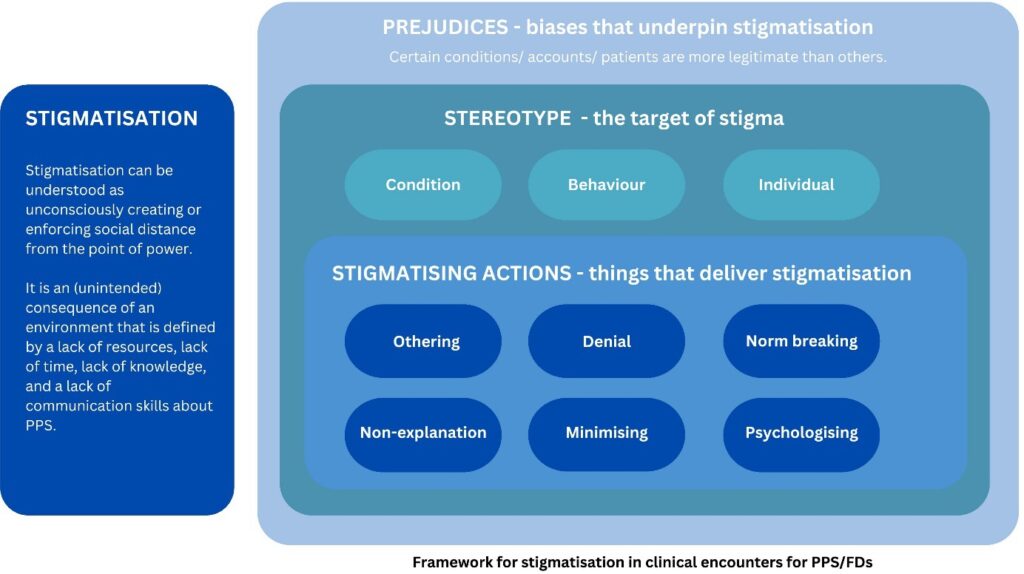

With this is mind, Treufeldt and colleagues set out to map how the stigma occurs in during the clinical consultation for patients with PSS/FD, more specifically – they set out to create a new actionable framework to aid understanding of stigmatisation during consultations, ultimately aiming to improve the consultation experiences for individuals seeking help for these problems, and their clinicians (Treufeldt, Burton, McGhie Fraser, 2024).

There is a pressing need for such a framework. Existing conceptual frameworks that inform stigma in healthcare mainly derive from mental illness models, social distance models (for example in infectious diseases), or other sociological models – none of which capture the nuances and complexities of the medical interaction so relevant for individuals with PSS/FD.

To do this – Treufeldt and colleagues used a ‘Best Fit Framework’ method (this framework allows to test and build on an existing established model). They first constructed an a priori stigma framework, by collating the key components from existing influential conceptual models after a broad literature search. They then used data from a published scoping review to revise the initial framework – this data comprised patient and clinician quotes concerning stigma in medical encounters (Treufeldt & Burton, 2024). They continued the process of iteratively re-mapping and testing the framework using this quote data, constructing the final framework with three core components: 1. Prejudice, 2. Negative Stereotypes, 3. Actions to Stigmatise.

The framework is outlined in Figure 1 below:

There are several examples throughout the paper that enliven the framework and demonstrate how stigma is being communicated:

Stereotyping the person: “… I have to admit that it comes down to my own prejudice. I hold it against this sort of patient to a certain degree, they’re soft, you have to put pressure on them so that they will liven up their act/…/I think that in cases of women with fibromyalgia you’re conditioned to think twice about granting them work leave.” [source 8] (General Practitioner perspective on patients with Fibromyalgia)

Actions: Norm breaking: “Three women noted that their physician told them to get drunk before having intercourse, as this would aid in their relaxation. As Maya (34 years old) recalled, “I did go to my gynaecologist, and I said, you know, ‘I’m having a really hard time having sex.’ And she was just saying, “You’re just nervous. You’re tensing up. Get drunk.” [source 9] (Patients experiencing sexual pain)

Actions: Psychologising: “The neurologist did not give me a diagnosis. Instead, he suggested that my mother organize an appointment to see Dr. X. When we rang to make the appointment, we realized that Dr. X was a psychologist. It was then that I realized that the neurologist thought that it was all in my head” [source 10] (Patient with non-epileptic seizures – current acceptable terminology Functional (dissociative) seizures)

Their framework demonstrates clearly where stigma is happening – for example – as shown – approaches that are perhaps well-intentioned in a bid to make light of symptoms and not cause worry end up being “norm breaking” and inappropriate. “Psychologising”- again might be a well-intentioned approach to explore relevant psychological factors, but carries with it negative implicit connotations, potentially resulting in the patient feeling disbelieved and doubted. These are just some of several specific areas that can be explored further and used as targets to create communication interventions for clinicians and combat these challenges.

When it comes to more practical implications of this framework – watch this space. The framework is currently being tested in a focus group study of patients. Through this process Treufeldt and colleagues can test its usefulness and validity– and crucially use it to 1) further increase the knowledge about stigmatising clinical encounters and 2) address specific communication issues in order to improve them.

In conclusion, this framework is timely, novel and useful. Medical communication has been persistently highlighted as a source of frustration and distress for individuals (and clinicians) in the realm of PSS/FD. However, it has not been mapped out in this way, and meaningful interventions to address it are lacking. This framework is a hopeful springboard to improve the experience of care for this group.

Caoimhe Mcloughlin is a Consultant-Liaison Psychiatrist who is undertaking a PhD in Stigma in Functional Neurological Disorder in the University of Edinburgh as part of the ETUDE program (Encompassing Training in fUnctional Disorders across Europe).

References

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 956673. The article reflects only the author’s view, the Agency is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.